In the last article in the series on influential Egyptian women, Ahram Online sheds light on the life of Nabaweya Moussa, known as the First Educator

16 March marks Egyptian Women’s Day for a good reason. On this day in 1919, 300 Egyptian women led by Huda Shaarawi marched against British occupation. One woman, Hamida Khalil, was killed, making her the first female martyr that day. On that same day four years later, Shaarawi led the march to form Egypt’s first feminist movement. The march progressed from then on.

This year, Ahram Online celebrates Egyptian Women’s Day in collaboration with the AUC Rare Books and Special Collection Library, by sharing the stories of inspiring Egyptian women who led the march for women’s rights in the country. Every Thursday, the biography of an inspiring Egyptian woman will be shared. After exploring the life of Huda Shaarawi (1879-1947), the woman behind the march, and Doria Shafik (1908-1975) the “Daughter of The Nile,” the life and struggle of Aziza Hussein (1919-2015) the “People’s Ambassador,” we end the series with a salute to Nabaweya Moussa (1886 -1951), the First Educator.

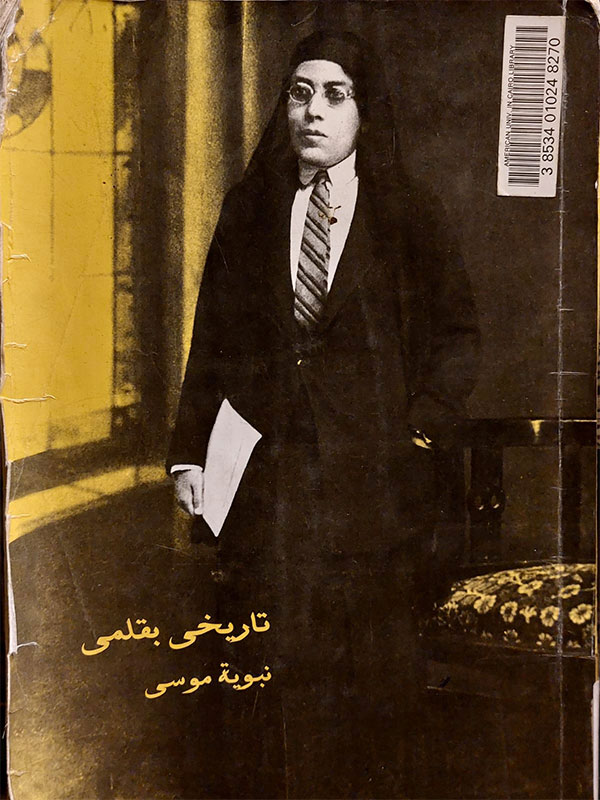

Nabaweya Moussa (1886 -1951)

Nabaweya Moussa made several groundbreaking achievements. She was the first Egyptian woman to attain her bachelor’s degree, become a tutor, become a woman principal, establish her own private schools, and acquire the Nile Badge. Her resilience and rebellion against traditions that constrained women in Egyptian society made her a prominent figure.

Poor handwriting, valuable content

In her memoirs titled My History Written by Myself, published in 1999 by the Women and Memory Forum, Moussa described her upbringing in a society that did not welcome education for women.

Her mother’s comment, “Teach them how to spin and weave but not calligraphy,” was her initial response when Nabaweya asked to learn how to read and write like her brother. Her wit and persistence at a very early age led her to grab her right to education by her own hands. Initially, she read from her older brother’s school books and learned all of the poems he recited at school. Her brother’s private Arabic tutor helped her to read Arabic.

When she was 13, she applied for her Ibtedaía (Sixth Primary) degree at Al-Saneya Girls’ School for Tutors. At that time, it was the highest form of education any Egyptian girl could attain. She stole the khytm (seal) of her mother to sign the papers of her registration behind her back, for her mother could not read or write. She even sold some of her own jewellery to pay for the fees.

The bold 13-year-old girl passed her exams along with two other girls in 1903. Her teachers were very impressed by the self-educated girl who was never taught how to use a pen properly, yet her writing style was excellent.

The first Egyptian woman principal

Soon, she was assigned the job of a teacher at Abbas Helmy School for a salary of EGP 6, while her male counterparts were given double her salary. When she questioned the discrimination, she was told that the men attained the bachelor’s degree while no Egyptian women did. And so she applied and managed to become the first Egyptian woman to attain her bachelor’s degree in 1907.

Known for her strictness and knowledge, she became the first Egyptian woman principal and then the head of inspectors at the Ministry of Education. She founded several schools for girls under her name in 1920, making her a pioneer in the field of Egyptian private schools for girls and eligible for the Nile Badge that was granted to her by king Fouad after visiting her schools and seeing her great impact on national education.

The feminist and patriotic writer

Moussa’s life was not solely focused on education. She was a creative writer whose essays were published under a false name “A Free Consciousness in a Sensitive Body” because, back in the day, it was prohibited to write in published papers while being a government employee. Her essays were often regarded as a subtle condemnation of the British occupation in Egypt, and they were so eloquent that they grabbed the attention of Egyptian political leader Saad Zaghloul at the time.

She founded her own women’s magazine, Al-Fatah, and became one of the key figures of the Egyptian feminist movement and one of two women who accompanied Huda Shaarawi to attend the first International Women Federation Conference in Rome in 1923.

As a feminist, Moussa adopted her own interpretation when it came to hijab and sofor. During this era, the word hijab did not mean head cover; it meant face cover, and sofor meant taking the face cover off. In her memoirs, she remembers a debate with a male counterpart who argued that women should cover their faces because their faces were seductive. She argued back, saying that there was no religious prohibition of showing a woman’s face, that Egyptian peasants do not cover their faces, and that the white transparent cloth barely covers the face. “Besides, since you men claim to be wiser and have better minds than women, then how come you are seduced by seeing their faces,” she wrote in her memoirs.

Source: Ahram